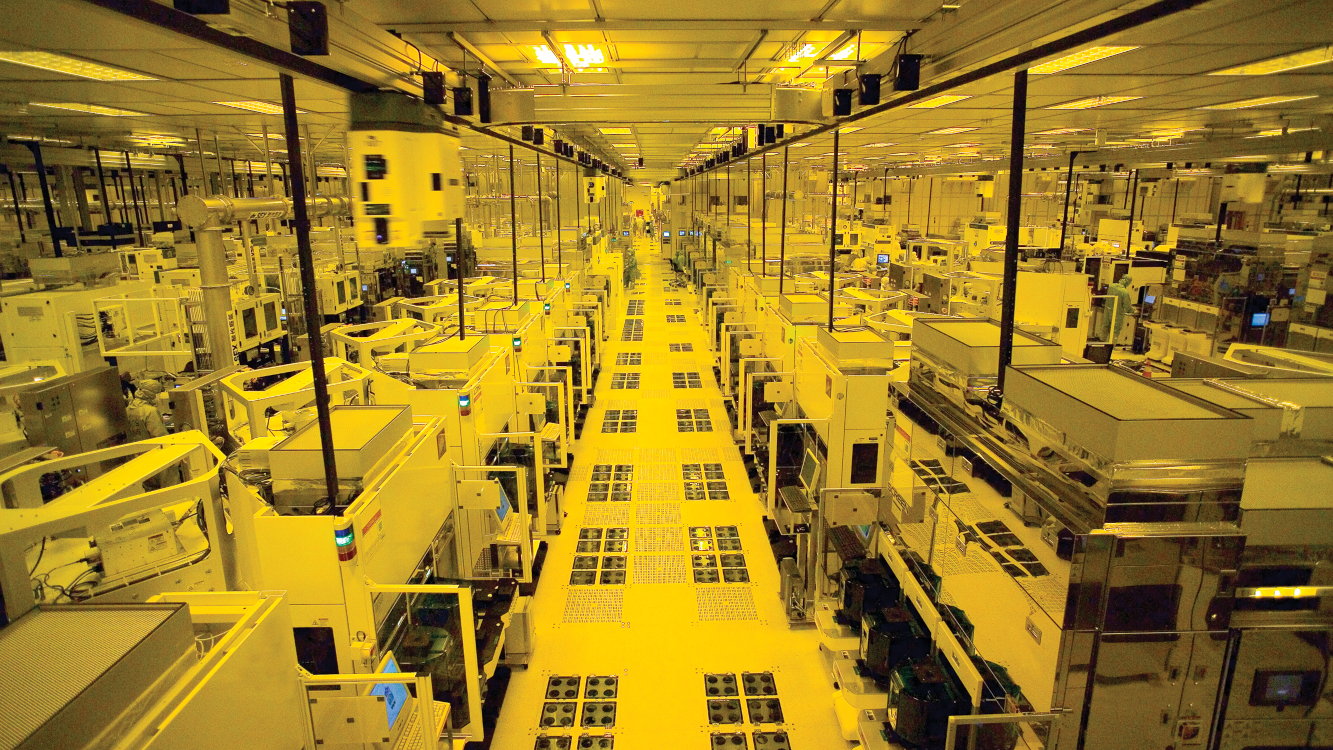

As aging LCD factories lose their economic footing, chipmakers are snapping up decommissioned display fabs to secure scarce cleanroom capacity for the AI era. The accelerating shift is reshaping global manufacturing as legacy digital signage panel lines are repurposed for next‑generation semiconductor production.

Cleanroom Gold Rush: Chipmakers Reclaim Old LCD Lines

The global display industry is undergoing one of its most profound structural shifts in decades. Aging LCD manufacturing lines – once symbols of industrial scale and national strategic pride – are rapidly losing viability as panel prices remain depressed and competition intensifies. According to a recent Digitimes report (paywall), major panel makers including AUO, Innolux and LG Display are now actively divesting older LCD fabs due to low production efficiency and relentless price pressure, while semiconductor giants such as TSMC, Micron, ASE and SK Hynix are emerging as eager buyers seeking ready-made cleanroom capacity to meet soaring AI‑era chip demand.

This week brought another major development when Sharp confirmed that majority owner Foxconn has withdrawn from plans to acquire one of Sharp’s key small‑display LCD factories in Japan. The deal collapsed amid persistent weakness in global LCD prices, prompting Sharp to halt production at the facility in August and offer voluntary retirement to 1,170 employees, as reported by Japan Today and Nikkei Asia. Sharp simultaneously announced the cancellation of a separate proposal to transfer large‑panel LCD technologies to an Indian partner – another setback in its long-running restructuring efforts. The decisions illustrate how even historically influential LCD players are now accelerating their withdrawal from traditional panel manufacturing.

The broader trend is unmistakable: the LCD business model, particularly for older-generation fabs, is collapsing under modern economic realities and political subsidies. Manufacturing LCD panels at scale – especially in Gen 10.5+ facilities – requires capital expenditure in the multi‑billion‑dollar range. Substantial portions of these investments go toward specialized machinery for TFT fabrication, substrate processing and color filter deposition, as well as the construction and maintenance of massive cleanroom complexes. As Digitimes notes, depreciation alone often accounts for up to one-third of total manufacturing costs, a structural burden that becomes prohibitive when panel prices are falling. Labor, in contrast, represents only a negligible share – roughly 2% – meaning cost‑cutting opportunities on the workforce side are limited, and location decisions increasingly depend on government subsidies and supply‑chain proximity rather than wages.

Stratacache stands out as a rare exception in the current wave of LCD divestments. While most display makers are abandoning legacy manufacturing sites, the US‑based digital signage company acquired a decommissioned Hynix Semiconductor plant on the West Coast, aiming to build up premium MicroLED production for automotive and other specialized applications rather than for mainstream digital signage. The ambitious plan, however, has been slowed by significant delays in fitting out the facility with the required production tools and equipment. When CEO Chris Riegel purchased the site at a bargain price, the scale of the coming AI boom – and the resulting global scramble for semiconductor equipment – was impossible to foresee. During the pandemic, cleanrooms and fabrication spaces were hardly in demand; today they are among the scarcest industrial assets.

Despite the challenges, Riegel remained confident when invidis met him at NRF earlier this year, expressing optimism that the necessary tools would arrive and MicroLED production could begin in the coming quarters. The project encapsulates both the opportunity and volatility shaping the new display and semiconductor landscape: what once seemed an undervalued asset has become a contested resource in a market transformed by AI‑driven demand.

Main Display Vendor have Exited Display Cell Manufacturing

The retreat from LCD production is particularly pronounced in Japan and Korea. In September 2024, LG Display announced the sale of its stake in a Chinese LCD facility to TCL CSOT for USD 1.5 billion as part of a shift toward higher‑margin OLED technologies. The transaction includes 80% of LG Display’s major LCD panel production line and 100% of its LCD module plant. TCL CSOT, already one of the world’s largest LCD makers, is further consolidating its position on the global stage. Sister-company TCL just announced a joint-venture with Sony for 2027, taking a majority stake into the then combined visual solution business.

Samsung, too, has completed its exit from LCD panel manufacturing, having sold its last LCD module plant to Chinese buyers – cementing China’s overwhelming dominance. Today, more than 90% of LCD modules are produced in China by only a handful of suppliers, a level of concentration unmatched in other display segments.

Downstream operations remain more geographically diversified. While panel production is concentrated in China, product design and management typically remain in Korea, Japan and Taiwan, with software development often handled by teams in India, Poland and other established software hubs. Final assembly is shaped largely by tariff structures: some professional displays for the EU market are assembled in Slovakia, Hungary or Poland, and those destined for North America are often completed in Mexico. Professional monitors without TV tuners face lower import duties in the EU, resulting in significant assembly volumes shifting to Vietnam, Indonesia and Malaysia.

Even Sharp’s iconic 10th‑generation Sakai plant – once a technological showcase—is being shut down and repurposed as an AI data center, reflecting a wider industry pivot toward computing infrastructure.

LCD Fabs Out, AI Cleanrooms In: Display Makers Retreat

Across the market, the message is clear: as demand for AI hardware, compute capacity and semiconductor cleanrooms surges, older LCD fabs are increasingly more valuable to chipmakers than to display manufacturers themselves. With depreciation-heavy cost structures and flatlining panel prices, traditional LCD production can no longer compete with the accelerating economics of advanced computing.

The realignment is reshaping the global display landscape. China now controls the vast majority of LCD capacity; Korean and Japanese manufacturers are pivoting aggressively toward OLED, microLED and AI‑driven applications; and semiconductor companies are seizing opportunities to convert legacy display facilities into next‑generation chip fabrication or packaging lines. What was once a cornerstone of consumer electronics manufacturing is being repurposed—sometimes literally—to power the next era of digital transformation.